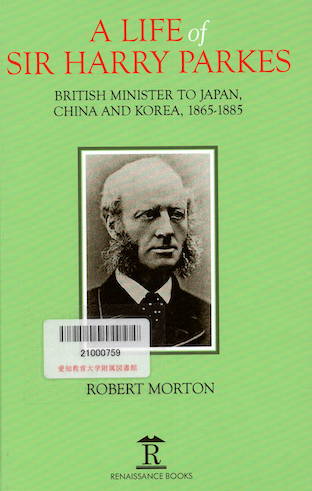

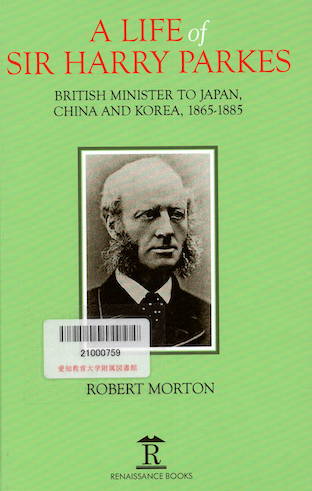

Robert Morton: A Life of Sir

Harry Parkes

I had come across writings about Sir Harry Parkes in the past,

including when I read

Isabella Bird's 'Unbeaten Tracks in Japan' about her travels in

Japan, as well as in books

about past British diplomats from 'The Japan Society'. However, I

realised how little I knew

about him when I read this biography.

Although born in a reasonably well-off family, he was orphaned. As

a result his 'working'

life began early and he was in China when he was only fourteen.

That was the beginning

of a rise to the highest diplomatic posts in China and Japan and

involvement in hugely

important events which connected those countries with Britain,

particularly the Second

Opium War and the 'opening up' of Japan after the Meiji

Restoration. He learned Chinese,

which helped make him relatively indispensable and as the writer

indicates, he "always

understood what was happening in Japan far better than any other

foreign representatives

(p.264)."

He was someone of his time, seen as paternalistic in dealing with

those Asian countries and

working from a point of view of British Empire era superiority. He

was described as someone

who was tenacious (didn't give up) and could seem to be arrogant

in asserting such ideas of

superiority, especially in insisting on the higher status of Queen

Victoria when dealing with

royalty, as he did in China, Japan and Korea.

He was a workaholic, who found it difficult to relax. That

combined with the effects of tropical

disease could have led to his death at 57, although that was not

unusual for those who had

diplomatic posting in locations challenging with challenging

climates. He was not always

popular with his subordinates and offended many people he dealt

with. However, the biography

shows how he loved his wife and family, although they were often

far apart. He also involved

his wife in the work he did and she reciprocated with interest and

involvement.

Particularly in his earlier years, his life was 'exciting', with

attacks and excitement and he appeared

to show no fear! He was also ready to be 'hands on' and not 'stand

on ceremony', as shown when

he was ready to demonstrate a system to allow a bosun's (a petty

officer on a ship) chair to move

across water from one shore to another. As the writer says, "It

seems extraordinary for a man of

Parkes' rank to have submitted himself to this - a Japanese

official would not have dreamt of doing

anything like that." (p.200-201). He was, after all, Sir Harry

Parkes, successively British Minister

to Japan and British Minister to China.

It was good to discover about his life. At the time, he was

honoured with a knighthood and

after his death a memorial was unveiled in London (at St Paul's

Cathedral) and a statue in Shanghai

(melted down during World War 2), but he has faded into the past.

Therefore, this biography

does much to recognise his importance.

See other

books which I have read.

Go back.