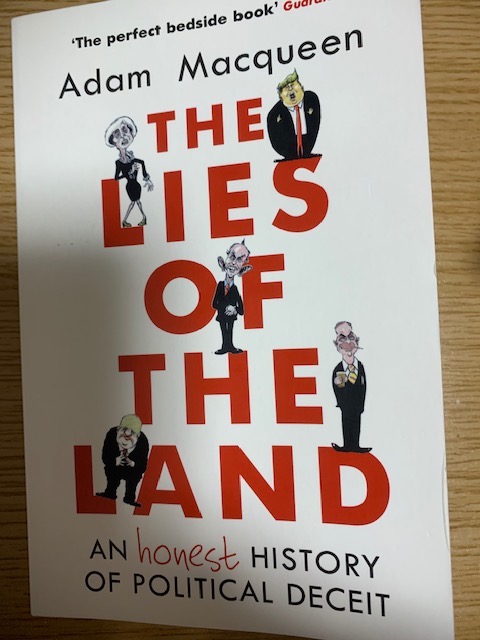

‘The Lies of the Land’ by Adam Macqueen (Atlantic

Books, 2018) is a play on the words in the expression ‘The Lie of

the Land’, which means how a situation is developing. Written by a

long-time contributor to the UK satirical magazine ‘Private Eye’,

it looks at how politicians have often been “economical with the

truth.” Most famously used by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert

Armstrong, in 1986, it is an indirect reference to ‘lying’.

‘The Lies of the Land’ by Adam Macqueen (Atlantic

Books, 2018) is a play on the words in the expression ‘The Lie of

the Land’, which means how a situation is developing. Written by a

long-time contributor to the UK satirical magazine ‘Private Eye’,

it looks at how politicians have often been “economical with the

truth.” Most famously used by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert

Armstrong, in 1986, it is an indirect reference to ‘lying’.

However, the writer of this book does not actually refer to that

instance. Rather, he looks at many other examples over the period

from the Second World War onwards. These are mostly in the U.K.,

but there are also some examples from the U.S., including the

famous Watergate episode in 1972. In that case, as the writer

indicates, “The weirdest thing about Watergate was how unnecessary

it all was. President Nixon’s approval ratings were on the up in

1972: they peaked for the year, at 62%, just a fortnight before

the burglary of the Democratic National Committee headquarters. He

would go on to win his second election that November by a

landslide.” (p.107) Needless to say, the most recent

incumbent of the White House, Donald Trump, is not left out by the

writer!

Examples from the U.K. particularly centre on some key but

contrasting, events, including the Suez Crisis in 1956. That led

to the resignation of then prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden, who

the author describes a continuing, “to lie through his teeth about

his foreknowledge of the invasion,” as when he said in parliament

on 20th December 1956 that he would, “say it quite bluntly to the

House, that there was not foreknowledge that Israel would attack

Egypt - there was not.” (p.27/32). Another example in the Middle

East concerned intervention in Iraq based on the claimed presence

of WMDs (weapons of mass destruction). Although the author

describes Tony Blair, who was then prime minister, as one of “our

best prime ministers”, along with Winston Churchill and Margaret

Thatcher, he indicates a resulting effect, that “Self-belief can

convince you that everyone else should believe you too. Then

things like empirical truth are for the little people.” (p.5) For

Blair, “Emotional truth counted for far more than historical

truth.” (p.223-224)

With this edition being published in 2018, the latest issue

leading to being “economical with the truth”, is Brexit, Britain’s

withdrawal from the European Union. It particularly focusses on

the ‘leavers’’ campaign which had the infamous promise to, “send

the EU 350 million pounds a week, let’s fund our NHS (National

Health Service) instead,” which appeared on the side of a campaign

bus. This figure was much challenged. As the writer indicates,

“But whichever way you looked at the sums, we sent the EU nothing

like that much money.”

Obviously, it is relatively easy to criticize, but much more

challenging to offer ways to overcome the perception that

politicians are always lying. He offers a few ideas, including a

ban on political donations, which would potentially to reduce lies

related to lobbying. However, he also notes new challenges, not

least the downside of the Internet and the rise of ‘truthiness’,

coined by U.S. satirist, Stephen Colbert, in 2005. This means that

people increasingly people believe in what, “people want to

believe.” That is undoubtedly going to be a major challenge to

deal with.

See the previous book which I wrote about.

‘The Lies of the Land’ by Adam Macqueen (Atlantic

Books, 2018) is a play on the words in the expression ‘The Lie of

the Land’, which means how a situation is developing. Written by a

long-time contributor to the UK satirical magazine ‘Private Eye’,

it looks at how politicians have often been “economical with the

truth.” Most famously used by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert

Armstrong, in 1986, it is an indirect reference to ‘lying’.

‘The Lies of the Land’ by Adam Macqueen (Atlantic

Books, 2018) is a play on the words in the expression ‘The Lie of

the Land’, which means how a situation is developing. Written by a

long-time contributor to the UK satirical magazine ‘Private Eye’,

it looks at how politicians have often been “economical with the

truth.” Most famously used by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert

Armstrong, in 1986, it is an indirect reference to ‘lying’.